This week, some notes half-way towards a thought. I’m hoping to continue trying to think about work a bit more over the coming weeks.

The opening move of Communists Like Us1 is to address the question of ‘work’. Communism needs to be ‘rescued’ from it’s disaster, and this disaster is specifically located in the question of work.

There are plenty of discussions that might emphasise the ‘refusal of work’ as a political strategy, and discuss it’s weaknesses or strengths, whether that be in terms of traditional strikes or in some other form2. The tension that these discussions often depend on is the one between workers and bosses, in one form or another. We might think that this tension is what is meant by the idea of ‘class struggle’. Whilst much of the class struggle is, indeed, taken up with the everyday conflict between worker and boss, at its heart the concept of class struggle is not a description of a situation of differing interests. Rather it points to the space in which the human social form is determined.

Underlying the point being made by Guattari and Negri is perhaps a more fundamental tension. What is this tension we encounter when we think about the concept of work? We might begin to get at this tension by asking about what kind of work we might want to do.

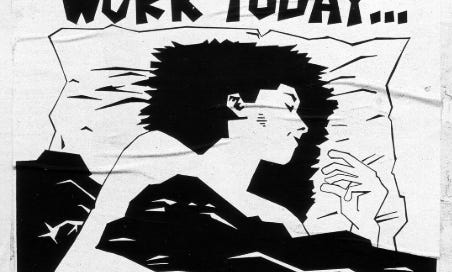

Often ‘work’ is something that appears in our lives as something that has to be done. Even if the goal is autonomously set, the actual work involved as a means to that goal might appear as something of a necessity, something of an imposition onto our lives. This is in some ways so obvious as to be our common sense. Work is ‘what has to be done, not what I want to do’. It has to be done because without getting on and doing our work we can’t enjoy the rest of our lives, we can’t afford the rest of our lives. Even the question, what kind of work might we want to do, can too quickly get caught in this common sense. The question is limited by what kind of options exist.

This goes all the way back to our encounter with work as children, whether through the way educational activity is framed as work or through the way someone might be asked to think about what kind of job they want, what kind of career options exist for them and so on. We transition from a space of play to the supposedly ‘serious’ world of work.

Underpinning this transition is the shift from an open social space of interaction (play) to one of social subjection (our contemporary social form of work). Within this framework some people might try to make their work meaningful, think of it as a vocation or as socially necessary, others might have little option other than to think of what work they can get as just something that pays the bills. Still, the widespread attitude is that work is something that has to be done. It’s a necessity, but one that we must submit to and impose on ourselves. For many this submission and self-imposition is even the sign of maturity and responsibility.

Guattari and Negri point to another possibility however, one that is - as they rightly note - bound up with the ideal of communism. Here is a clear example of this other vision of work:

“...communism is the establishment of a communal life style in which individuality is recognized and truly liberated, not merely opposed to the collective. That's the most important lesson: that the construction of healthy communities begins and ends with unique personalities, that the collective potential is realized only when the singular is free. This insight is fundamental to the liberation of work.”3

This shifts any sense of communism away from something like ‘equality’, particularly with regard wealth and incomes, towards the more fundamental target of the social form, what Marx called the “economically given social period”4. At one point Guattari and Negri explicitly reject the idea of communism as some kind of so-called wealth sharing - “this communism must be more than just the sharing of wealth (who wants all this shit?)”5.

The distinction between work and play is used by some to try and find a way out of an account of work as the imposition of necessity. If we can make work creative, empowering and fulfilling, and throw in a little fun and laughter, then maybe it will seem like we’re playing again. For example, someone who wants to make their office a social space, where they find human interaction with their ‘work mates’, might be thought of as trying to develop the positive potentials of work as a kind of play space. They might find themselves sharing humourous memes on a WhatsApp work chat, or enjoying their secret santa festivities that HR carefully monitor and regulate. They might be positive that they enjoy their workplace, they could have people they describe as work wives or work husbands and spend hours recounting the tales of the office clown or terror. They might use the word ‘fun’, as though work could be as good as play, just a mature, responsible, adult version.

The problem, however, is that all of this seems either a delusion or a denial. It can all collapse the moment the redundancies become imminent, or when that new manager takes a dislike to them. They are at the mercy of a contingent kindness. So long as they can smile and laugh it’s all wine and roses, but they must first of all comply with the hidden rules, avoid confrontation, do as you are told and - above all - don’t think that you’re at work because you need the money. The game is fun only as long as we believe we want to play it.

There is another option, however. Instead of the distinction being one between work and play - the one a necessity, the other a freedom - there is a more positive concept of work. Guattari and Negri point to this when they make the following claim:

Paradoxical as it seems, work can be liberated because it is essentially the one human mode of existence which is simultaneously collective, rational and interdependent. It generates solidarity.6

This is a fascinating description of work and quite a strange one. The properties ascribed to work appear to describe something closer to a traditional concept of politics, not work.

Communists Like Us: new spaces of liberty, new lines of aliance - with a ‘Postscript 1990’ by Toni Negri, Semiotext 1990, translated by Michael Ryan. Felix Guattari and Toni Negri. The original French edition is called Nouvelles espaces de liberte, published in 1985.

See some of the articles that come back from a search of LibCom - https://libcom.org/search?search_api_fulltext=refusal+of+work

Communists Like Us, p.17, Semiotext 1990

Althusser has an epigraph from Marx at the head of his famous essay Marxism and Humanism. The full citation from Marx is “my analytical method does not start from man but from the economically given social period”. Standing at the head of Althusser’s essay it is intended to mark the scientific Marx, the one who has gone beyond the framework of vague humanism (dismissed as mere ideology) and opened the world of scientific understanding of the social.

ibid, p.13

ibid, p.14

A World of Work #2

This continues some loose thinking around the concept of work, starting from a reading of Communists Like Us by Felix Guattari and Toni Negri.