These notes work through the text in order, with some discussion and the occasional aside. They aim to help in reading Negri’s text and are not a substantial critique or evaluation of Negri’s argument, although I will comment on that argument as I proceed.

Setting things up and framing the analysis

Negri’s first claim is that the birth of the Grundrisse (notebooks) is not a neutral moment of theoretical abstraction. The notebooks begin in the face of crisis, the so-called panic of 1857 in the US. This market panic, which rapidly spreads across the USA and beyond, is the first to indicate the global connections of capital. It’s also the first to arrive after a period of capital speculation, in this case in the form of investments into railroads. Within a few years (1861) the USA will descend into Civil War.

If the financial crisis of 1857 and subsequent political crisis is the context for Marx’s work in the notebooks, then perhaps this allows us to make some sense of Negri’s claim that “the imminence of catastrophe is not simply the occasion of an historical forecast; it becomes a practico-political synthesis” (MBM, 2)1. For Negri, this is in the form of the appearance on the scene of the fundamental opposition to capital that he names as ‘the possibility of the party’. “The crisis reactivates subjectivity and makes it appear in all of its revolutionary potentiality at a level determined by the development of the productive forces” (ibid).

If we draw an analogy between the crisis of 1857 and the financial crash of 2008 we can maybe understand a little better what’s going on. The 2008 crash, which revealed both the dubious and arcane practices of financial institutions, also revealed the way they are bound into our lives. In that instance it showed that capital had begun to re-organise our housing situation, increasing the rate of profit that could be extracted from this aspect of our lives. The crash would affect a whole range of economic activity, but it also revealed that housing had clearly moved from being something socially useful to something that was simply a means of financial profit and capital leverage. For the sub-prime mortgage lenders, housing wasn’t the issue, simply the asset value and what they could use that asset for in terms of profit. The fact that in this instance the assets were people homes and lives was irrelevant, or had become irrelevant.

For a brief while, the financial crash also raised the question of the failures of capitalism. It gave birth to a new interest in Marx, and it broke the sense of capitalism having somehow simply defeated socialism with the fall of the Soviet Union. A new phase of consciousness - of subjectivity as Negri calls it - arose, one which was able to mark a new moment. Historically, another step was taken - there was the fall in 1989, now there was the crash of 2008.

What’s noticeable is that these two moments are probably more fundamental to the contemporary dynamics of capital than the political moment of 9-11, which opened up the ‘war on terror’. That political moment is still playing out, no doubt - we’ve seen the latest instance of its effect with the recent banning of PA in the UK - but the more fundamental structural shifts are probably more accurately marked as between 1989 and 2008.

The other interesting moment in these first few pages can be found in the role of Hegel. Marx notes that he had been reminded of Hegel and in particular the ‘Logic’. Now it’s not clear from the Negri text and its reference which particular Logic is being referred to, although I’m going to assume it’s the Greater Logic (The Science of Logic) rather than the shorter Lesser Logic (the logic section of the Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences). Marx indicates that he has used the method of Hegel, drawn from the Logic, in his notebooks. What might that actually mean?

We won’t get very far if we try and answer this by simply using the word ‘dialectic’. This is, of course, exactly what Negri does. He describes Marx as producing a great synthesis between practice and theory, inspired by the crisis of capital that is erupting around him. “The synthesis signifies the linkages among the punctual and catastrophic character of the crisis, the rules of development, and the dynamics of subjectivity. Where these different terms are linked, the dialectic rules.” (ibid). This use of the concept of ‘dialectic’ is unhelpful and doesn’t clarify anything. We could replace it with something like ‘reciprocal determination’ or ‘dialogue between elements’ or ‘interplay’ or some other vague notion, all of which would be clearer than the semi-mystical use of this word ‘dialectic’, but this would still, perhaps, miss the point. What exactly might Marx have taken from Hegel in this instance?

Two things, I think, stand out. The first is the concept of totality, the second that of internal dynamics or development. Marx reads capitalism as a totality. This is very clear from the opening pages of the notebooks which begin with a discussion of the way traditional capitalist economists separate out different aspects of the social and economic whole, production separated from distribution for example. Marx wants to counter this with an analysis that poses all aspects of the economic and social as being part of one whole. This is what totalisation means, to take it all, in total, as part of one thing, to analyse the situation as a totality rather than as separate and autonomous areas with their own distinct rules.

The second key element is of an internal dynamics or development. This is seen most clearly in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, where we find his fantasy story telling us about a mystical journey of consciousness from opposition to integration, from ignorance to knowledge, reaching its final moment - unsurprisingly - in Hegel and his particular brand of Christian thought. In the Logic (both Lesser and Greater) we find a similar kind of story, except this time it’s not posed in terms of consciousness but in terms of ‘being’. The logics offer an ontology, an account of the nature and ways of being. The logic is a story of the way things are, and it’s a grand unifying story, a grand narrative. Marx picks up this aspect and integrates it into his method, shifting the core dynamics from one of spirit to that of human production and reproduction.

It’s perhaps interesting, therefore, that Negri will be trying to return subjectivity into Marx in his reading. Instead of simply being a description of capitalist development in terms of the means of production, as something inhuman almost, Negri wants to emphasise the key role of subjectivity (consciousness) again. In Marx’s terminology of means of production and relations of production, perhaps this is a move to return those relations of production to the front and centre and, in the process, counter-act a rather mechanical analysis, one that sometimes gets called ‘economistic’.

Next in Negri’s text comes a short descriptive account of the origins of the notebooks, listing their time of writing. Most notable here is the relatively short time span of their composition, between August 1957 and February 1859, with some other notes from the start of the decade added in. Negri then locates his particular focus, on notebook M and the texts written between October 1857 and Spring 1858. He then offers a short summary of the argumentative line in the notebooks, arguing that “the Grundrisse appears at first sight to be a largely incomplete and fragmented work; but this doesn’t mean that the notebooks do not have a center and a very strong dynamic” (MBM, 4).

The argumentative line that Negri sketches out appears interesting, although I cannot offer any judgement on it at this point. Again, noting points of interest and attention only, it’s worth thinking about how this line of argument is thought to conclude. Where does Marx go with his analysis according to Negri? Unsurprisingly perhaps, as this will be a key feature of Negri’s reading, it ends with a vital role for subjectivity (consciousness) - “in the seventh notebook the crisis of the law of value and its transformations (once again the theme of profit) leads us to a more precise definition of the objective and subjective conditions of the production of capital” (ibid).

At this point in Negri’s text, we find the first arrival of a central claim that he wants to make with regard to his reading of the Grundrisse. It appears in the following passage:

We thus see, throughout the Grundrisse, a forward movement in the theory, a more and more constraining movement which permits us to perceive the fundamental moment constituted by the antagonism between the collective worker and the collective capitalist, an antagonism which appears in the form of the crisis. (MBM, 4 - emphasis in original)

This point about the antagonism between collective subjects is an important shift from a reading of capital as a kind of inexorable machine of growth, or some strange kind of playing out of an abstract ‘law of value’. The reading Negri wants to make places class struggle at the centre, not abstract laws. Antagonism between collective subjects, between classes, is the core of the analysis, but an antagonism that appears in the form of crisis. This implies that any analysis of a crisis, be it 1857 or 2008, will miss something crucial if it begins from some supposedly internal dynamic of capital because the crisis itself reveals the antagonistic relationship. Any analysis of crisis that cannot show how that antagonism is developing is one that misses the most central dynamic. This is what Marx is doing, Negri thinks, and why it’s a ‘theoretico-practical synthesis’. It speaks to not just how the system works but to how people themselves, as collective subjects, act as a key factor of that situation, not just as passive respondents to an abstract active force.

Alongside this keyword ‘antagonism’, the other keyword of Negri will be ‘exploitation’, but more on this later. It’s briefly mentioned after the talk about antagonism, but for the moment Negri moves on to make another point.

First major claim of Lesson 1 - how people misunderstand Capital.

The central claim of this first lesson begins to be apparent at this point in the text. Roughly it goes something like this. If we read the notebooks as unfinished and preparatory to Capital, which is how they have been read so far, then we miss something fundamental and will misunderstand Capital. In fact the claim is stronger than one of ‘misunderstanding’ - for Negri there are political questions of interpretation at stake in the reading.

Again, roughly and crudely, the notebooks offer a dynamic theory in which the working class is a central player, a key element of the dynamic, and the question of revolutionary subjectivity (consciousness) cannot be found in Capital on its own. Indeed the claim that Capital is the ‘finished product’ and as such should be read as the truth in contrast to the loose and provisional preparatory notebooks (the ‘philological reading’) hides a reactionary political attitude which wants to minimise the role of that revolutionary subjectivity within the dynamics of the system (MBM pp 5 and 8). This produces the kind of Marxist that thinks they can treat capitalism as a scientific object of study that operates according to impersonal laws that we, as subjects, have no option other than to obey. This is a position that ends up being used as an excuse to argue against revolution.

This is perhaps the radical aspect of Negri’s reading of the notebooks. His interpretation, or more accurately his re-interpretation, of the notebooks not only shifts the way they should be read in an academic sense, it also adds a political stake to that reading with the claim that the existing interpretations end up producing a reactionary strategic thought.

Next time someone tells you that you need to read Capital to understand Marx, you can reply that if they haven’t read the notebooks then they’ve only got half the picture, and the wrong half at that (at least according to Negri).

Second major claim of Lesson 1 - surplus value and antagonism

In the next few paragraphs we find Negri again trying to politicise the stakes of interpretation rather than engage in philological discussion. What is important about the theory of surplus value? This is the question at the heart of what Negri is doing. Is it simply an explanation for ‘profit’ and the most noticeable feature of capitalist economic activity (‘profit motive’)? Or does the understanding of surplus value immediately imply a political struggle and an antagonistic subjectivity? For Negri it will be the latter.

One brief aside here. At one point we find Negri use the following substitutive phrase, which is evidence of an equivalence of meaning within an authors work. “Historical materialism - the specified analysis of the class composition - is given new content here…” (MBM, 9). If you ever wondered what ‘class compsition’ means for Negri, here’s a key moment of its use that offers a base definition connected to Marx’s concepts.

Returning to the discussion of surplus value, we see again the keyword of antagonism - in this case ‘fundamental antagonism’ - alongside that concept of totality that we mentioned earlier and that is drawn from Hegel’s ‘Logic’. Only by understanding surplus value in terms of antagonism can one begin to get to grips with it. In fact Negri makes a broader and more sweeping claim.

Outside of antagonism, not only is there no movement, but the categories do not even exist. (MBM,9)

Why is this sweeping? Put bluntly because it denies any kind of objective, neutral analytical position. One cannot in reality be a neutral academic Marxist, the very concept is impossible, because an analysis grounded in Marxist concepts such as surplus value is always already part of the antagonistic relations - in other words, the analysis is always either part of the proletarian or the bourgeois side, and neutrality is precisely a form of bourgeois bullshit. There is no understanding of surplus value that is not itself part of the antagonism and so the question is always to be asked, which side of the antagonism does the analysis come from?

After sketching out this major claim about antagonism and surplus value Negri indicates that it will take the rest of the work to ‘demonstrate’ it - in other words, to give the arguments and evidence for his claim. Having staked out his main points of disagreement or ‘rupture’ with other interpretations, he goes on to sketch out his other major points. This is a good summary and plan of where the lessons will go. These will include (1) the role of money, (2) our definition of work2, (3) the nature of an antagonistic theory as being open, (4) an understanding of marxism as a ‘science of crisis and subversion’, (5) a Marxist definion of communism and (6) a definition of the working class.

An additional moment - determinant abstraction and tendency

Having outlined these key moments of his analysis he also adds another factor, this time directly to do with method (MBM, 12). We’ve already mentioned the reference to Marx using the method of Hegel’s Logic, but now Negri wants to make something like the following claim: Hegel’s method in the Logic is transformed in Marx’s notebooks into a method of determinant abstraction and tendency.

These are plainly concepts at a philosophical or more sepecifically, an epistemological level, that is, at a level of abstraction that inform how we can think about something and what kind of knowledge proceedures are available for truth.

Broadly speaking we might hear what are technically called (in philosophy) epistemological concerns in talk about things like frameworks of thought, or paradigms or even standpoints and it is at this level that the concepts of determinant abstraction and tendency are put forward, at an epistemological level.

The easiest way of thinking of these is in terms of criteria for truth, or if you like, the rules of the game of asking questions and giving answers. Science and religion, for example, have different criteria of truth and as such do not share epistemological criteria. So we can have a religious understanding of science, or a scientific understanding of religion, in both cases giving quite distinct and coherent results. We may, in addition, validate or use only one form of epistemological criteria and deny the other as valid and this is the big question with a method - is it a viable, useful or realistic method or is it just a way of someone telling a particular kind of story?

The question of method, however, does not need to be decided before we do analysis. We do not need to agree with an epistemology in order to be able to understand it and the same here, we do not need to agree with a method in order to understand it. We do need to understand the method being used, however, in order to use the right criteria to judge whether an argument is coherent (not true, coherent).

So the question would be, if Negri is right about the method that Marx is using, then what difference might this make to understanding Marx’s arguments?

What would this method of determinant abstraction and tendency mean? In Negri’s hands it appears to be something like the following - the moment of determinant abstraction is one in which we have to be very specific about what’s actually and concretely happening (determinant) to a particular abstraction (ie: surplus value) - in Negri’s words it “subjectifies the abstraction”. What kind of changes in wages are taking place, what kind of changes in the division of labour, what kind of shifts in housing, or housework, or childcare are taking place and such like. What’s actually happening and how would we find out? These are the questions of determinant abstraction.

On the other hand the method of tendency is one of asking about what kind of options exist and what kind of directions are developing. Is childcare becoming more or less gendered? Are workplaces becoming more or less surveilled? How does the working age shift amongst one country to another within the division of labour? What kinds of resistance can be seen in the different problems that employers discuss when talking about managing workforces? These are questions of tendency. These tendencies, moreoever, are not finished - they’re tendencies, not facts, potential routes things might take not predictions and as such “cannot be enclosed within any dialectical totality or logical unity” (MBM, 12). This denial of the posibility of totality is interesting here but something to come back to another time.

There’s a beautiful couple of lines at this moment in the text that I want to highlight, more as a placeholder than anything I want to immediately discuss.

The determination is always the basis of all significance, of all tension, of all tendencies. As for the method, it is the violent breath that infuses the totality of the research and constantly determines new foundations on which it can move forward again. (MBM, 12)

Marx beyond Marx but which Marx?

The Marx that goes beyond Marx is not a marxist going beyond Marx. It’s not Negri who goes beyond Marx nor any other interpeter of Marx, real actual and communist or academic and intellectual. No, one of the most interesting theses of Negri is that the notebooks themselves are Marx going beyond Marx, they are a moment in which the retreat into the formulations and structure of Capital are exceeded by the author and method of Capital.

This is to deny, explicitly, any claims that the notebooks are part of an early Marx as opposed to a mature scientific Marx of the later works. It’s also to deny any philological arguments as to which is the more authoritative text, the early one or the later published version. Most importantly it’s also denying that the wildness of the notebooks is a source of error that should be purged in the cold light or a rational day. Rather the wildness itself is Marx beyond Marx. This is Marx in connection with matter, in a strange materialist delirium that becomes a “delirium of the material”.

What’s fascinating about this particular formulation is how much it appears to owe to the methodology of schizoanalysis articulated by Deleuze and Guattari within their two volume work Capitalism and Schizophrenia (i.e.; Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus). There the role of delirium is precisely this one played out, according to Negri, within the notebooks. Delirium is an epistemological tool within schizoanalysis, not a site of error but a source of productive connection with matter, just as it is here in the Grundrisse. It’s interesting to note this early appearnce of schizoanalytic concepts in Negri and and I’d be surprised if these formulations (MDM, 16) aren’t a direct result of an encounter - and taking up of - the methodology of Anti-Oedipus.

Reiterating the major claim of Lesson 1 - the political reading

Let us be clear: it is not a question of an abstract polemic against Capital: each of us was born in the reflection and theoretical consciousness of the class hate which we experience in studying Capital3. (MBM, 18)

The final pages of lesson one amount to laying out the interpetative field and we find Negri positioning himself in terms of debts and conflicts. He notably appears to suggest his reading runs counter to Hobsbawn, with whom he opened this lesson, and that his reading of the notebooks as embedded in the American crisis of 1857 is a debt to Sergio Bologna’s reading. He also gives an historical context to the interpretation of Rosdolsky and others, as well as giving credit to “a young comrade, Hans Jurgen Krahl” for his capacity to “perceive in the categorical development of the Grundrisse the constituting moments of the class struggle”.

Amongst this rendering of accounts and contextualisation of his own reading we also find once again the idea that there are clear political stakes involved here, not just academic or philological ones. This passage perhaps makes the point most clearly:

In so far as the Grundrisse flows through Capital, we can be happy. The concepts of Capital are, in this case, adequate for understanding the development of the antagonism. Nevertheless, there are several cases where the categories of Capital do not function in this way: as a result we can sometimes think that an exacerbated objectivism can be legitimated by a strict rading of Capital. Thus the movement of the Grundrisse toward Capital is a happy process; we cannot say the same of a reverse movement.

And if that’s not clear enough, particularly for contemporary reading groups of Capital, then let’s make it even clearer.

We can only reconquer a correct reading of Capital (not for the painstaking conscience of the intellectual, but for the revolutionary conscience of the masses) if we subject it to the critique of the Grundrisse, if we reread it through the categorical apparatus of the Grundrisse, which is traversed throughout by the insurmountable antagonism led by the capacity of the proletariat.

Negri goes on to pose the reading Grundrisse as the real source of the revolution from below in direct contrast and political opposition to a revolution from above and as such we find that the key to Negri’s reading is not, strictly speaking, a matter of text, but crucially but a matter of revolutionary politics and strategy.

References are to Marx beyond Marx: lessons on the Grundrisse, Antonio Negri, Autonomedia 1991, abbreviated as MBM. A PDF of the text is available here.

These discussion around the definition of work are why I’ve picked up this Negri text, being led here by the broader thinking around work I was doing earlier in the year and which is on pause whilst I continue the study of Negri, alongside study of the contemporary moment of ‘Artificial Intelligence’. You can find those posts here, or a printed version of some of them here.

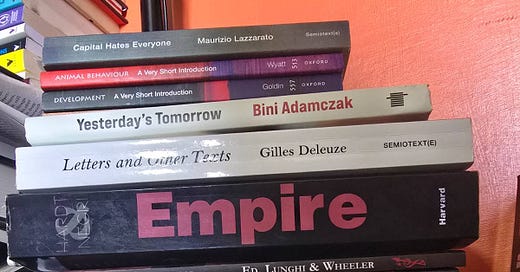

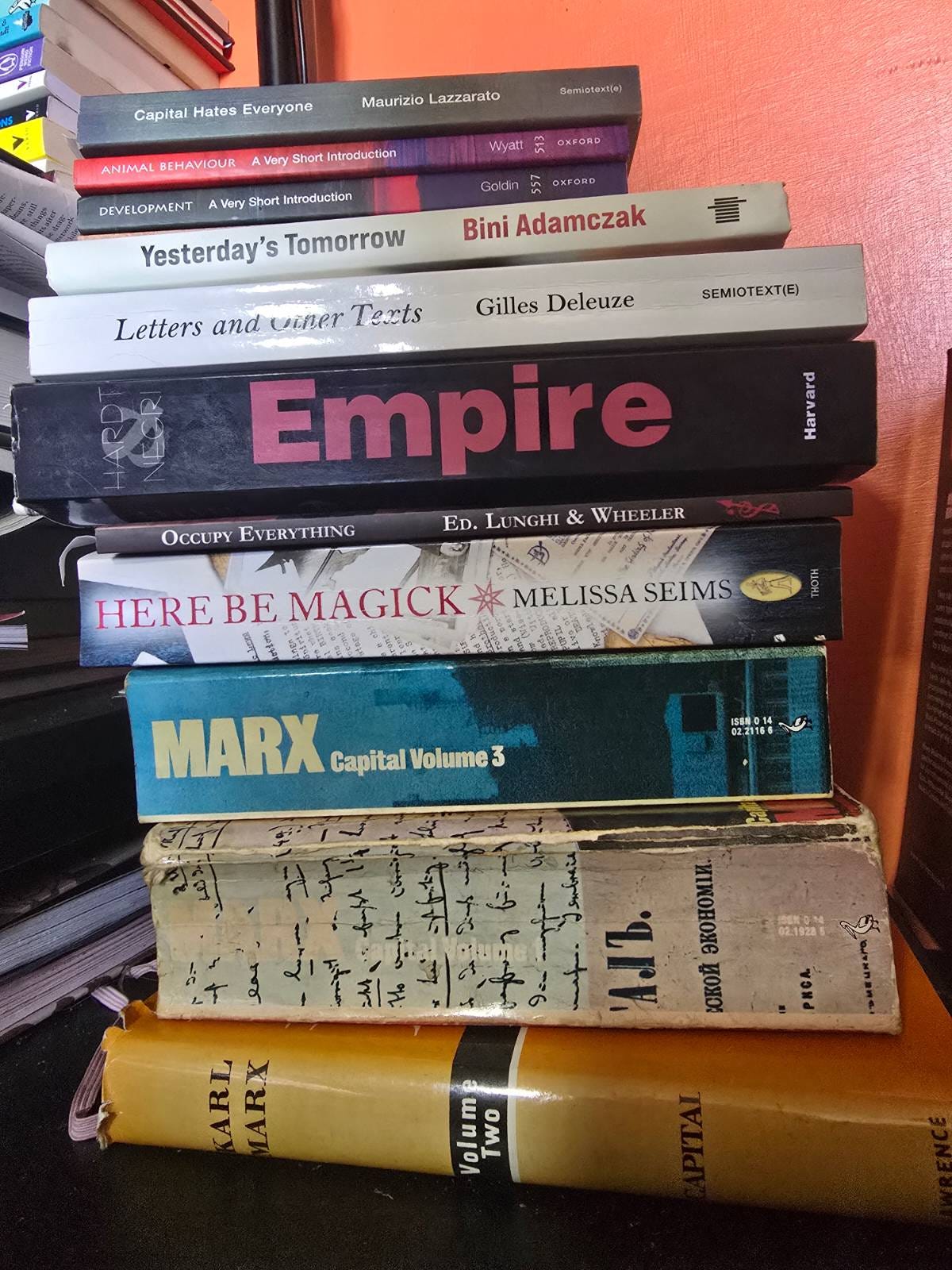

I love this particular quote, not least because I began trying to read Capital when I was thirteen or fourteen years of age. I want to my local small bookshop that I visited regularly and in this curious little place got them to order in the three volumes of Capital from Lawrence and Wishart, which I then spent about a year paying for on lay-away, from pocket money made doing a paper round. I still have these, in their stark orange covers, one of wwhich is shown in an image above, even though I tend to use my beaten up Penguin copies - also shown n that image - far more for actual work. They sit on my desk or on my bookshelves as a kind of totemic reality of forty years of engagement with Marx. These first readings of Marx were confused, and confusing, and intensely boring at times, my auto-didactic proletarian self driven by almost atavistic desires rather than intellectual questions, interspersed and animated precisely by a need to study born precisely from that class hatred that I already had and that found it’s reason and future within Marx’s words.