On the concept of study as a mode of becoming-X: learning from the Free University Brighton (FUB)

notes for a talk at the conference ‘The Reverse Side, July 8/9/10 2019

The modern capitalist University has always functioned as a key institution of the state apparatus and continues to do so. The question is not how to defend the University but how to revolutionise it, how to explode the hierarchy, privilege and power of those - including those who see themselves as radical - who maintain and reproduce the mode of institutional learning that the University represents. This involves breaking open and decolonising not just the curriculum but the ‘mode of institution’ itself. The new task involves constituting the University anew, revolutionising the very concept of the University - in, against and beyond the University as it is instituted. But what do we throw out and what do we keep?

The Example of FUB - a brief general account

FUB has been going since 2012. It’s still going. I got involved when it started. A small group of academics, mostly connected to the Humanities department at the University of Brighton, were discussing how to offer something like a ‘free degree’ as a practical response to the rise in tuition fees across the UK. When I was made redundant from the University of Greenwich, where I had been a lecturer in philosophy for a decade, I decided that I wasn’t happy working in the mainstream University any more and that I would involve myself in FUB instead.

The project was always practical rather than theoretical. We developed and delivered courses and classes, building an alternative educational space. This involved a website, a mailing list and classes - many originally held in cafe’s and other free spaces that could be found. The core idea was that all we needed was students and a facilitator in the same space. That was it. It was never quite as simple as that, whilst at the same timje always being just that simple. And there was to be no money involved. Indeed the slogan of FUB was and is, “education for love, not money”.

A few years into the project we began to think about how we could reflect on our activity. This took place through a film project. We brought in a facilitator - a video and film editor (who happened to be my partner) - and they sat in a room with students and other tutors from FUB and decided the group collectively decided what they wanted to do. The result was a series of interviews with FUB members of all kinds, which was edited into a documentary of sorts.

Collective study or knowledge acquisition

One of the things that numerous participants talked about in the film project was the fact that FUB produced a strong sense of community. The traditional University often refers to itself as a community but this feels rather hollow, reminding me of that horrible phrase ‘we’re all in it together’ that is used to justify austerity. In the case of FUB how is this ‘community’ constituted?

Communities are constituted in large part through the boundaries and borders that define the nature of membership and belonging. These boundaries can take many forms, and are often informal, as is the case with FUB. One of the recurrent questions that has occurred in the last few years is this notion of membership, or joining. In response to the question, ‘how do I join FUB’ the answer is ‘sign up to our communication platform and attend class’. In other words, you join by being involved.

Sometimes it’s clear that people struggle with this degree of informality, where membership is not something that can be paid for, not something you receive in the form of a little ID card in exchange for filling in a form and paying some specific amount of exchange value, rather membership in FUB is grounded in participation. Even more than in a traditional University, membership is constituted by activity, most concretely, the activity of attending class, and every other structure of FUB is intended as support structures for classes.

What is it that takes place in a class however? We don’t have any formal requirements. Each class is autonomous. So what, if anything, is shared across the variety of activities that constitute the classes. The driving dynamic of the class is ‘collective study’. It is this simple practice, of studying together the same themes or within the same horizon, that constitutes everything.

Here it’s perhaps important to make a distinction. I was trained as a philosopher and the making of distinctions is probably the single most important tool in any philosophers toolbox. It’s the heart of actual philosophical activity. The distinction between ‘collective study’ and ‘knowledge acquisition’ is the one that matters here. To make a distinction we need to identify things such as different properties, implications, inferences.

In the case of the distinction between collective study and knowledge acquisition, the latter can occur through study but doesn’t actually require it. In addition, knowledge acquisition can only be tested through performance, with criteria of ‘success’ and some process of judgement of value. Collective study, in contrast, is ‘tested’ - or shown to exist - through participation and presence.

This is important if we think of the mainstream University as being focused on exactly this, ‘knowledge acquisition’, rather than on collective study. In particular we encounter the rather curious problem that in practice the capacity to perform knowledge over-determines the traditional University. The academic - whether student or tutor - needs to appear to know. They may, of course, actually know something as well, but this is not a necessary condition of appearing to know. To perform knowledge is, in a world of knowledge acquisition, enough to be taken to know, at least on the face of it and for as long as the appearance can be maintained. This is part of the core problem of the failure of the mainstream University model.

Ivan Illich, two watersheds and anti-production.

In his ‘Tools for Conviviality’ Ivan Illich describes two watersheds in healthcare. The first watershed is the moment at which it is a 50/50 chance that someone seeking medical treatment will be seen by a graduate from a medical school, rather than a traditional healer of some kind. This occurs in 1913 in Illich’s account, although in reality this is likely to vary depending on location. The second watershed occurs when the cure becomes the source of a new sickness, in the case of the modern medical profession these new diseases are called ‘iatrogenic’, or ‘doctor-induced’.

These two watersheds mark threshold moments, the first moment being one of the institution of a new form (distinguished from its beginning, or constitution), the second moment being that of an anti production.

Describing the origins of the FGERI (Federation of Groups for Institutional Study and Research) Anne Querrien describes anti-production in the following way:

The simple idea behind this federation was that, in every domain where intellectual labour is deployed - and the labour of the manual worker is also intellectual labour - the workers encounter forces that Felix called forces of anti-production, that is, social forces that prevented them from reaching the best possible realisation of whatever it was they planned to do.

In Querriens description the forces or anti production appear to be primarily exogenous to a practice. Talking about her work studying teaching practices she says,

Exploitation showed itself in the practices of throwing obstacles in their way, of putting on the brakes and of repression, even during the course of productive activities, in an attempt by the dominant society to manage everybody’s time and to prevent them from benefiting from the freedom to enjoy a variety of things. (emphasis added).

Later she mentions, with regard schools, how anti-production operated by using “the strong students to persecute the poor ones, instead of mobilising them to ensure that the poor ones learn too.”

This concept of anti-production appears close to the second watershed moment of Illich.

It is sufficient to recognize the existence of these two watersheds in order to gain a fresh perspective on our present social crisis. In one decade several major institutions have moved jointly over their second watershed. Schools are losing their claim to be effective tools to provide education; cars have ceased to be effective tools for mass transportation; the assembly line has ceased to be an acceptable mode of production.

What is interesting about Illich’s account perhaps is that the second watershed moments don’t seem simply exogenous, but have a curious, almost endogenous character. Even in Illich, however, it is not simply the practices of schools, or cars, or assembly lines that produce the anti-production effects, rather it is the scale of the production.

For Illich this is a result of a mass industrial society, and he calls for a return to something like a ‘natural scale’, which brings with it all the difficulties of deciding quite what this ‘natural scale’ might be. Putting aside the ‘natural’ element here, what I would want to retain is the relation of scale to anti-production effects.

If the University is over-determined by its capacity to perform knowledge, what I want to suggest is that this performance - which in principle could be a kind of ‘showing that you can do something’ - has reached a point at which the scale of the performance of knowledge becomes self-destructive1.

Is this a rather convoluted way of saying, some things can only be done within specific scales of operation?

Linguistic Imperialism and the University mode.

An aside on Lazzarato and linguistic imperialism.

The modern University (in terms of the Humanities at least, perhaps a more complicated picture emerges with regard to the sciences) is caught within a knowledge performance that is dominated by what Lazzarato has called a ‘linguistic imperialism’. The reconstruction of the University (as a revolutionary force?) must begin from the position of the destruction of the empty, self-aggrandising chatter of linguistic imperialism.

In Lazzarato’s essay ‘Exiting language’, semiotic systems and the production of subjectivity in Felix Guattari, the point is made that “Structuralism is dead. But what actualised its paradigm, ‘language’, is very much alive. And, most surprisingly, it is thriving in the critical theory that developed in the 1980s and 1990s following the great theoretical innovations of the 1960s and 1970s that had mapped out escape routes from structuralism.” (EL 504). This problematic is the background for Lazzarato’s exposition of some of Guattari’s ideas, which are presented as an alternative to this ‘language paradigm’.

Virno, Ranciere, Butler and Agamben are all identified as key players in the continuing production and reproduction of this linguistic imperialism that is located as having its roots in Aristotle, as well as its contemporary constructions in Arendt and ‘analytical philosophy’. The reason that language is still crucial for so many is in large measure as an “attempt to get away from the reductionist hypotheses inherited from Marxism that viewed it [language] as a mere superstructure or ideological artefact”.

For the linguistic imperialists “language is transformed along with its affects into the very origin of the social and society” (ibid). Language is viewed as productive and with the rise of ‘cognitive work’ this becomes even more confused, as those looking to produce the ‘new society’ appear to focus more and more on language, language use and language transformation as strategies for ‘radical action’. As Lazzarato points out, “all these theories, despite their critical intent, keep us still and forever inside a ‘logocentric’ world, in which subjectivity and enunciation remain ‘human all too human’.” (EL 505) Against this Lazzarato poses the centrality of the machinic and it is here that Guattari comes to the fore for him as a key thinker of the machine.

One of the most beautiful and eloquent presentations of this idea of the rule of the machine comes in William Burroughs ‘ah pook is here’, a text that has long settled into my own unconscious as an organising refrain. In this Burroughs says:

We have a new type of rule now. Not one man rule, or rule of aristocracy, or plutocracy, but of small groups elevated to positions of absolute power by random pressures and subject to political and economic factors that leave little room for decision. They are representatives of abstract forces who’ve reached power through surrender of self. The iron-willed dictator is a thing of the past. There will be no more Stalins, no more Hitlers. The rulers of this most insecure of all worlds are rulers by accident - inept, frightened pilots at the controls of a vast machine they cannot understand, calling in experts to tell them which buttons to push.

This Burroughs text plays an important role in one of Deleuze’s more political statements, Postscript on the societies of control, where it is Burroughs who is identified as offering the name that Deleuze then takes up to describe our contemporary political situation – “’Control’ is the name Burroughs proposes as a new term for the new monster” (PS 4).

It might be objected that ‘control’, in being offered as a ‘new name’ for our contemporary political situation, relies on a linguistic priority of some kind, something along the lines of ‘the importance and power of naming things’ as a principle underpinning a set of tactics. This objection reveals the danger of linguistic imperialism, however, since it shows us the mode of capture involved in such imperialism. This mode of capture moves from the prevalent need to engage linguistic structures when developing tactics of resistance to an implicit and unwarranted assumption that any tactic of resistance must engage with linguistic structures, establishing a principle of capture that coordinates the various dynamics of linguistic imperialism. In the end it is necessary to assert that resistance is not primarily linguistic, and language is neither the most important nor the most necessary site of resistance. Rather it is ‘understanding’ – in a broad sense of the term – that underpins resistance and it is a false prejudice to assume that understanding can be brought under the control of language.

There is, alongside the principle of capture of linguistic imperialism, a pragmatic tendency towards the (over) prioritisation of language as a site of resistance. This concerns the cultural construction of a ‘space of reason’ as primarily a linguistic domain. To resist linguistic imperialism appears - to the imperialist - as a resistance to reason. If some element of the social structure is resisting rule and yet cannot explain that resistance, cannot justify and rationalise it to ‘explain themselves’, then their resistance becomes something to be explained. People (more precisely, one part of the social, often the dominant part) want to understand why, for example, some other people do something that is ‘disobedient’ and if the disobedient don’t speak, or are not heard, then that resistance will end up being explained by someone other than the resistant, an explanation that is one more part of the machinic process of ‘knowledge production’.

With the spread of ethnography and ethnographic practices and the cross-over between the University and movements of resistance, almost no space is left outside the net of linguistic imperialism. Academics mine the unspoken without concern for the recuperation of resistance that occurs in its transformation from practices of understanding to practices of saying. Contemporary resistance movements, perhaps more than at any point in time, are defenceless against the redescriptions of linguistic imperialism.

At one point University culture, in being tied closely to the establishment practices of rulership, formed a clear horizon of combat, a space of reasons and ideas that almost by definition was the enemy of resistance. Now, however, its cultural space is less clearly one of being a simple an ally of the rulers. The cultural space of University is self-defined as a space of reason, rather than rulership, even though its broad social function has never changed. The function of the University is to ‘establish the rule’ and this function surpasses the content of that rule. This functional drive to ‘establish the rule’, to explain, to make things seem as if they had a ‘why?’, this drive of the University cannot but conflict with the drive that is ‘resistance to rule’, so it becomes its’ friend, therapist, master, advocate, expert, voice. Yet this is the friendship of domestication.

‘Rulership’ and ‘rule’ – as the primary objects of resistance – constitute a distinct and different horizon from the ‘unreasonable’ or ‘stupid’. Their confusion, or the confused overlapping of these two horizons, produces a problem for anyone involved in trying to resist capitalism, specifically contemporary capitalism.

What is it that resistance to capitalism resists? Stupidity, cruelty, greed, inequality? The unending ecological self-destruction of mass manufacturing? Such a resistance, to stupidity, to what might be thought of as the stupidity of capitalism, is often the form in which resistance appears to itself, but it does so because the resistance is framed, particularly by the University, as a rational or justifiable or explicable action. Resistance to stupidity makes that act of resistance appear as the rational, humane, sane, sensible, self-gratifyingly correct thing to do.

Capitalism, however, is not stupid. There’s no scenario in which it can be made sane. It cannot be ‘humane’, or caring, or rational, because it has no intentions that can be changed, no drive that can be moderated, only axioms of reproduction. Capitalism is a particular and specific structure of social organisation that arose, as it were, accidentally and inadvertently because it enables some to benefit, usually temporarily, in its reproduction. Capitalism is a structure of organised functions the reproduction of which presents itself as natural, inevitable. It is not, on its own terms, unreasonable or stupid or cruel or self-destructive since these terms have minimal purchase on the functions inside the capitalist framework. The axiom or rule of ‘making profit’ (otherwise known as the ‘extraction of surplus value’), embodied in a specific set of humans, may encounter the embodied, socialised values of those humans who may attempt to align their values with that axiom, but if such an alignment isn’t possible then the axiom still wins. Profit or die, this is one of the key rules.

Here, in the ‘rules of the game’, we can find the need to develop and nurture resistance to rule, to rulership, rather than to stupidity. Here, also, we can find the ‘very origin of society’, in the reproduction of a rule and rulership. Capitalism is a new form of rule, one that coordinates rulership and rule along a specific axis, in a specific direction, eroding a pathway of parameters within which any rule that allows the drive to profit to do its work is functionally reproduced for as long as it enables that drive to be put to work.

Just as the water wheel harnessed the waters power, so capitalism harnesses the river of reproductive labour that arises from the human.

Sometimes we are presented with an image of capitalism as a landscape or topography that has increasingly covered everything over, leaving no room, no place, to escape. Yet the better image is perhaps of the torrential river, picking up boulders that carve lines through mountains, pounding rocks into sand, transforming plains into fertile fields. Just as the water wheel harnessed the waters power, so capitalism harnesses the river of reproductive labour that arises from the human. This is no story of natural or economic determinism but rather a story of a force that sweeps us along in its current until we gasp for air and strike out for land, or at least for a hand-hold...

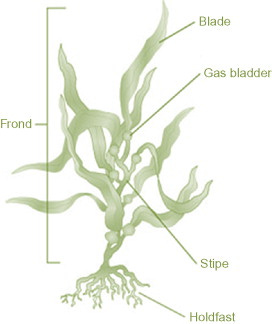

Only to find ourselves as seaweed, with only a small holdfast to anchor us to a territory as the ocean flows through and around us.

Scale, Knowledge and Convivial Tools

Let us assume that knowledge is something that can only be encountered at a specific scale.

Return to the idea of collective study and knowledge performance versus collective study.

If William Burroughs offers us an image of our contemporary rulers as being subject to “a vast machine they cannot understand”, then Ivan Illich offers us another perspective on the machine that might be used to get a handle on the machinic elements of the University, features that are both key to revolutionising the University as well as being features that are outside the domain of the structural and symbolic. The distinction between machine and structure that Guattari makes is crucial here, because the machinic elements are critical moments in the constitution of a space of collective study, to the social relationships that are almost pre-requisites for such a machine to function.

In his work on ‘conviviality’ Illich says the following:

Tools are intrinsic to social relationships. An individual relates himself in action to his society through the use of tools that he actively masters or by which he is passively acted upon. To the degree that he masters his tools, he can invest the world with his meaning; to the degree that he is mastered by his tools, the shape of the tool determines his own self-image. Convivial tools are those which give each person who uses them the greatest opportunity to enrich the environment with the fruits of his or her vision. Industrial tools deny this possibility to those who use them and they allow the designers to determine the meaning and expectations of others. Most tools today cannot be used in a convivial fashion (emphasis added).

Illich goes on to say that “the concept of ownership cannot be applied to a tool that cannot be controlled.”

Learning from FUB and study as becoming-X2.

A key feature of FUB is the fact that the joy of teaching is central - tutors like to teach there, they find it a breathing space in many cases - in part because of the size, in part because of the associated lack of bureaucracy, in part because of the students and the freedom for their practice.

At the heart of the activity is the class - a space of study, one that can be collectively owned, because its function is not subsumed in a vast edu-factory but is rather part of a developing community.

The focus on study allows the intimate relationship between the personal effects of education and the political role of a revolutionised University to be placed centre stage.

How can the experience of University feel liberating - perhaps more so for working class students and ‘those who succeed’ - if the institution is oppressive by being functional to capitalism? It does so because the opening up to new worlds and works encountered in the process of study opens the possibility of new worlds (existential territories). This is the becoming-X, the encounter with the practice of becoming (rather than knowing). This becoming-X, however, is caught within the traps of the contemporary University.

Traps? This becoming-X is caught by an anti production force, in this case the becoming-academic. To be an academic is not inherently a positive, any more than to be a doctor - recall the problem of the iatrogenic disease.

The most interesting aspect of study lies in its capacity to undermine alienation, and in this capacity it is one of the central pillars of any reconstituted University. Study operates as a mode of ‘becoming-X’, producing a specific form of intimate relationship to body, self and time that is - within modern capitalism - able to offer a route of resistance to the problem of being ideologically and infomatically overwhelmed.

But it can only do so in convivial space that is able to resist the forces of anti production.

Central to such conviviality are questions of scale, of small, relaxed and fluid spaces that coalesce around study as their function.

There need be no collapse into elitism, into privilege and scarcity, simply because of the need for the small, the informal and the fluid.

The University must slip into the Ocean, reconstituted as a seaweed field of classes, spaces of collective study.

Free Subscriptions Available and Welcomed.

Bibliography

EL - Maurizio Lazzarato, ‘Exiting Language’, semiotic systems and the production of subjectivity in Felix Guattari, in Cognitive architecture: from bio-politics to noo-politics. Architecture & Mind in the age of communication and information, Rotterdam 2010, pp.502-521, accessed online. The same line is to be found in his book Signs and machines – capitalism and the production of subjectivity, Semiotext 2014, p57, (henceforth referred to as SM).

AP – William Burroughs, Ah Pook is here and other texts, Calder 1979. A rather groovy animation of ‘ah pook’ is available and well worth a look.

PS – Gilles Deleuze, Postscript on the societies of control, October, Vol.59, 1992, pp.3-7, accessed online.

AQ - Anne Querrien and Constantin Boundas, Anne Querrien, La Borde, Guattari and Left Movements in France, 1965-81, in Deleuze Studies, Vol.10 Issue 3, 2016, pp 395-416

TC - Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality, accessed online at http://www.davidtinapple.com/illich/1973_tools_for_convivality.html

This is not simply a matter of numbers, although that is part of it - in 1970 50K First Degrees, 12.9K Higher degrees - this goes up to 68K / 19k in 1980, 77k and 31k in 1990 - then 243k/86k in 2000, 278k/125k in 2005, 330k/182k in 2010 and 350k/194k in 2011.

As percentage of population participating in HE: 3.4% in 1950, 8.4% in 1970, 19.3% in 1990 and 33% in 2000 - source: House of Commons Library, Education: Historical statistics Standard Note: SN/SG/4252, Last updated: 27 November 2012 Author: Paul Bolton, Social & General Statistics.

This idea of the becoming-X, in its connection to study, needs developing more and elsewhere. At this point it is a marker for somewhere to go next when thinking about the University, study and knowledge.

I'm studying on a humanistic counselling degree at a principled (but capitalist) institute academically underwritten by a standard capitalist University. While the intimacy of the class is powerfully nurturing, the written work I produce is entirely conformist and conforming. My power to engage fruitfully is hampered by polarities of radical authenticity and limited academic acceptability. However, through meaningful labour with others, I am, slowly, becoming.